China Works to Secure Maritime Access to Middle Eastern and African Oil

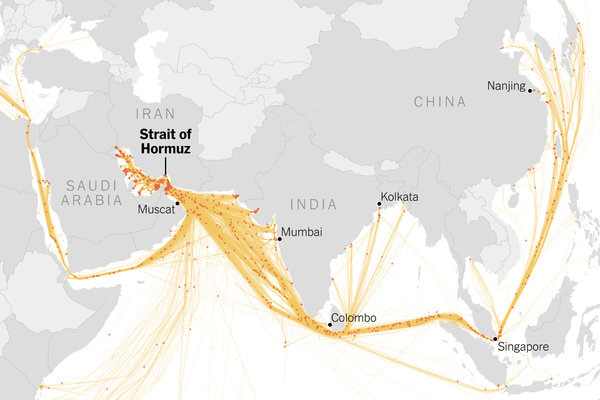

China’s rapid industrial expansion and tremendous economic growth have increased its national demand for hydrocarbon resources, further heightening the importance of Middle Eastern and African oil supplies to its energy security strategy. In terms of trade, the route running the South China Sea through the Strait of Malacca constitutes Beijing’s most important sea line of communication and provides access to major foreign energy producers. It is the shortest and most efficient passage to the Persian Gulf and facilitates about 80 percent of China’s oil imports.

The Asian giant has become the world’s largest crude oil importer and is now on trajectory to surpass the United States as the leading refiner. However, China’s heavy reliance on foreign energy supplies, as well as its dependence on highly concentrated trade arteries transiting the Malacca Strait, are considerable geostrategic vulnerabilities. Recognizing this, Beijing has taken steps to diversify its energy sources, promote renewables, and develop alternate import options such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), though it remains unclear just how effective these efforts will ultimately be.

In 2003, President Hu Jintao described China’s predicament as the “Malacca Dilemma,” citing the risk of a naval blockade by a foreign adversary. Intensifying pressure from the United States, tensions with India, threats posed by non-state actors such as pirates and militants, as well as a host of other considerations have since impelled Beijing to better secure its sea lanes.

And from Beijing’s standpoint, there is obvious reason for concern: U.S. strategists speak openly about disrupting China’s maritime trade flows in the event of a conflict. In a recent interview, for instance, one known researcher touted America’s ability to interfere with China’s “access to oil and other raw materials” in the Indo-Pacific; “especially in the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf,” he remarked.

Naturally, China is taking threats to its vital supply chains very seriously and looks to establish greater sea control near key trade routes, while also growing its power projection and far seas capabilities to secure its expanding interests abroad.

China is developing a blue water navy, building out an international network of logistical bases, and investing in port construction projects in various coastal states — much of the latter under the rubric of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which includes a Maritime Silk Road and increasing security component.

The Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) notes,

In view of China’s ballooning investments and growing Chinese expat communities in risk-prone countries, Beijing has become convinced that it has to take security concerns along the BRI routes in its own hands.

The securitization effort begins at home with coastal militarization and the development of its national maritime apparatus. China is building a sophisticated and modern missile umbrella with an emphasis on anti-access/area-denial capabilities in the Asia Pacific, boasts 5th-generation fighter aircraft, and now champions the world’s largest navy, though the U.S. still leads in terms of gross tonnage. Beijing is increasing its offshore footprint and is boosting its regional naval posture with an eye toward achieving primacy within the first island chain.

Beijing’s strategic priorities are certainly weighted in favor of its more geographically proximate security concerns, yet it is also working concurrently to establish a global network of maritime logistical hubs — a requisite for a blue water fleet.

Research by the U.S. Naval War College highlights this process:

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has been laying the organizational groundwork for far seas operations for nearly two decades, developing logistical and command infrastructure to support a “near seas defense and far seas protection” strategy.

China’s Maritime Silk Road encompasses the Malacca route, spans the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and rounds the Horn of Africa. China has already established a naval base in Djibouti, on the Horn’s littoral, and is reportedly scouting additional locations in South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. It has also staked, developed, and built island structures throughout the South China Sea and has equipped them with the infrastructure necessary to host and service its naval assets. Beijing’s 9-Dash Line territorial claim in the South China Sea, which includes the militarized Paracel and Spratly Islands, covers the majority of its sea lines of communication leading to the Malacca Strait.

The enlarged scope of China’s security vision was a notable theme in its 2015 defense white paper:

In the new circumstances, the national security issues facing China encompass far more subjects, extend over a greater range, and cover a longer time span than at any time in the country’s history.

…

With the growth of China’s national interests, its national security is more vulnerable to international and regional turmoil, terrorism, piracy, serious natural disasters and epidemics, and the security of overseas interests concerning energy and resources, strategic sea lines of communication (SLOCs), as well as institutions, personnel and assets abroad, has become an imminent issue.

The report emphasized the imperative of adapting to the rapidly changing global security environment:

The PLA Navy (PLAN) will gradually shift its focus from “offshore waters defense” to the combination of “offshore waters defense” with “open seas protection,” and build a combined, multi-functional and efficient marine combat force structure.

In its drive to become a regional hegemon, Beijing has dramatically increased its defense budget in what has been called the “most rapid, sustained, peacetime military buildup since the 1930s.” China aims to “complete national defense and military modernization by 2035” and develop a “world-class military by mid-century.”

China is becoming markedly more assertive abroad, is exerting greater influence over an expanded geographical range, and is moving to further protect its regional and global interests. The intensifying security competition with the United States is likely to only accelerate these trends.

The maritime domain will continue to be of particular importance to China’s Indo-Pacific strategy as well as its energy security policy going forward. Beijing will rely heavily upon the PLA Navy to protect sea lanes, project power, and respond to threats and crises around the world.